SQUARE 1

Her

So we broke up. People saw it coming. How are things with you and Max? they'd ask. I tried to lie, Same old, same old. I've never been a good liar; my face betrays my sentiment. People nodded, knowingly. Best of luck, they'd say. And so it went.

Him

I met her in the line at T.J. Maxx. We bought identical pairs of men's socks. In the parking lot, I told her my name and she smiled. She waved the socks between us and gestured toward the store marquee. That, she said, Is a double coincidence.

This is what she wrote on his back with her finger while he slept:

The moon was pastried in the sky like a Nilla wafer.

Not Him

I finally ended it the day before our second anniversary. I wanted Max and I to have something to look forward to, not to look back on. It made sense to me then. I was reading a lot of Emerson, transcendental flux and such. So I didn't want our anniversary to mark any sort of cycle. I wanted linearity, progression, a freedom not limited by our past. A new beginning, I said, That's all. But Max, because he's Max, didn't care to dwell on such significance. He was more concerned with whether or not we could get out of our lease.

Not Her

Things were great in the beginning. I bought her a stuffed hippopotamus. She named it Wilbur and hugged it in her sleep until its snout went crooked. We pretended Wilbur was our child, playing house and making jokes about his day at school. We cooked a lot, too, tried different recipes together. She made awful dumplings, but I ate them with a smile. Early on I told my friends, This is the girl I'm going to marry. I made bets, promises. I sized her finger while she slept. I taped notes to the bottom of her Nalgene bottle, so she could read them while she drank. I called her from work, just to say hello. I bought her flowers every week. For the first few months, she even watered them.

SQUARE 2

Her

So what was wrong exactly? They always said the best relationships were in and out; that graduate students shouldn't date other academics; instead we had to look beyond the university. Enter Max. He had a job; a dog; a protestant work ethic. In short, he was self-reliant; not in Thoreau's sense of the word (Max wasn't about to build a shed). Max was Emersonian, Franklinesque—his books were balanced (my books were strewn across the bedroom floor). What was it, then? In a word: sex. We were after different things. In bed I wanted minstrelsy, subversion, pomp. I wanted everything, and not just anything would do. My desires were complex, while his were not. I wanted jouissance, replete and never-ending. He wanted, simply, me.

Him

I want bubblegum, she said. I've got some Juicy Fruit, I said. Juji fruit? she asked. The train was loud. No, I said, Juicy Fruit. Oh, she said. She checked her watch. I want bubblegum, she said, Not Juicy Fruit.

This is what her dreams were like:

a gender is a gender is a gender is a product of intelligible diachronic processes reified as an a priori object-in-itself is a gender is the product of intelligible diachronic processes reified as an a priori object-in-itself is a gender verb a * has been indefinite article sex-enactment was indefinite article stylized repetition "congealed-over-time" to produce the effect of prediscursiveness will be an onto-epistemological paradox shrouded in semantic angst is a gender is a gender is a gender is

Not Him

Oh, right. At his Fourth of July faculty picnic in Millennium Park, he kissed some slut named home-wrecker.

Not Her

One time I said Where's the beef? and she laughed so hard she snorted popcorn up her nose. She blew it into a tissue and I said Yuck.

SQUARE 3

Her

Mise en scene: the shower, with a brush. I'm not wearing any paint, he said. It's edible, I said. No paint, he said, No way. So I protested: How can I be Betsy Ross if you won't be the flag? This is perverse! he said. Why can't we just be ourselves? Because I'm Queen Dido on a spire! I'm Paris fucking Hilton on a binge. No, he said, You're you: I want you. He tried to hold me. I backed away. Me? I said, I'm me? Then who the hell are you?

Him

I would hold her socks but resist the urge to smell them; sometimes her shoes even, so small and well kept.

This is what she ciphered with her finger on the frosted window of the Red Line train:

Hung from brackets, Edmund H. perceives the world at large; the world, in turn, perceives the matter of the object in the—; Heidegger removes a Jew in 1941; the empty sphere that resonates exists as this: infinity perceived as the object of its own digression. Somewhere in an alleyway in Freiberg now a cat says moo and then a [ ] shadowy and thick glides across the River Asterisk.

Not Him

What's this word mean? he asked. Vita. Then Aleatoric. Vermilion. Anabasis. Casuistic. Diurnal. Yet another. It means to rub against someone in public, I said. The celestial frottage of astronauts. Oh, he said. He read my poem again, with care. When he finished, he shrugged and tossed the notebook on our bed. I still don't get it, babe, he said. I grabbed the sheet of paper and, with a humph, stomped into the bathroom, locked the door.

Not Her

We watched an improv show near Wrigley. I think I could do that, I said when we got home. What, she said, Drive a cab? No, I said, Be funny like that. You're funny, she said. Yeah, I said, But up on stage. Maybe you could take a class, she said.

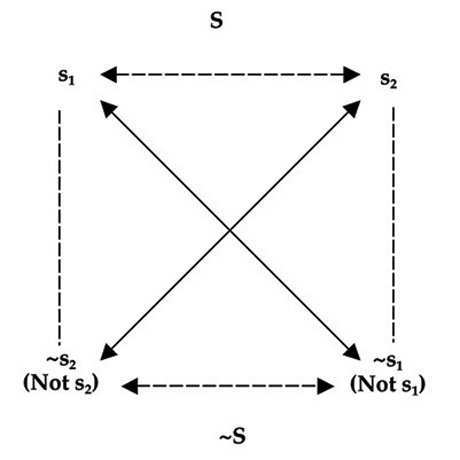

INTERSECT: The Crux of Their Dilemma

This doesn't, he said, Shed light on anything. Read it aloud, she said. The visual representation of the logical articulation of any semantic category or, in other words, the visual representation of the CONSTITUTIVE MODEL describing the elementary structure of signification. There, she said, That's a semiotic square. That's a ridiculous bit of nonsense, he said. No it isn't. Yeah, he said, It is. Keep reading, she said. In the Greimassian model, given a unit of sense S1 (e.g. rich), it signifies in terms of relations with its contradictory ~S1 (e.g. not rich), its contrary S2 (e.g. poor), and the contrary of S2 (~S2, e.g. not poor). Exactly, she said, It's clear as day. He closed the book emphatically. It's [nonsense], he said. [~S1], she said. Well, he said, It certainly doesn't make any S2. It doesn't not make S2, she said. Yes, he said, Deliberately so. You're suggesting, she said, That Gerald Prince defines a "semiotic square" in a way that purposefully creates a S2 of S1? ~S2 of, he said, Just S1! There's no S2 in any of this! He jumped up and made to leave; she took a deep breath. You just don't get it! they both cried out. It was then he grabbed the book and, turning away from her, chucked it out the balcony door where it fell into the empty courtyard pool below.

[Text and image source: Prince, Gerald. A Dictionary of Narratology. Rev. ed. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 2003.]

SQUARE 4

Her

He shaved his beard for me, you know; because it scraped my neck when we had sex. He came out of the bathroom with a big grin on his face. He looked like a pumpkin. Oh, I said. He waited, fresh and alcoholic, eyebrows raised. I guess, I said and paused. I don't know. I tried to smile, but it was too late. He shook his head. Of course! he huffed and threw his hands up in the air. He shut the bathroom door and I looked down at the book on my lap, breathed deeply, waiting.

Him

I'm going to make a sound, I said, And I want you to translate it. Her head lay flat against the stone, my hand on her hair. Ok, she said. Bwawk! I said. A noun, she said, A way in which to be perceived by sand. Good, I said, Try this one: floop-swee. Verb, she said, To cause to be dismayed. I stroked her forehead, her cheeks. I think you ought to marry me, I said. Adjective, she said, To tend to press the issue. The sun set behind the city; the lake grew dark, the rocks beneath the surface cinereous and dull. Grabble, I said. That's a word, she said, and we left.

This is what he never thought about:

Read Goethe beneath a cherry tree. Read Bukowski in a bus terminal. Don't read Shakespeare. There's no place like the beach for Lawrence Durrell. Read Virgil in the candlelight. Read Henry with a High Life; read Henry David with a full-body exam; read Horkheimer with a donut; slam dunk it in the margins with Vladi Spivak; Book yer flight to D.C. with Laurence Tureaud; the Prison Bitch, birth thereof; Fartor Refartus . . .

Not Him

I whispered in his ear: Rice-a-roni, the San Francis-coooo treat! But he just laid there, snoring like a toad. I said it over and over again, but nothing happened. After twenty minutes, I closed my eyes and started counting. One thousand one hundred and sixty snores later and it was morning. The alarm went off, he yawned. He nuzzled the side of my neck. Sleep well? he asked. Like a baby, I said.

Not Her

We took the train in the wrong direction. We'll be on time, I said. But the train didn't stop at the next station. It ran express toward Evanston. On the platform at the Howard stop, she tapped her foot until I touched her leg. She brushed me off and we stood beside each other silently. We could rent a movie, I said when the train finally came.

SQUARE 5

Her

What do you love about me? I asked him. He didn't think too long about it. Everything, he said. We were in the grocery store, buying coffee, ice cream, bread. I stepped into the main isle. Even this? I asked and turned my palms up toward the ceiling, raised the roof. I made woot-woot noises while I danced, and people noticed. He pretended not to care, nonchalantly tossed a bag of Seattle's Best into the cart and walked away. I caught up with him at the deli, and when I tried to hold his hand he blushed. You're weird, I said. Me? he balked. He pushed my hand away, tried acting cool. But he couldn't hide his smile.

Him

She was always doing something strange in bed. From time to time I'd go along with it, but nothing seemed to make her happy. Even when she got her way, she'd start to cry; she'd stare at herself in the mirror, at her breasts, her hips. She'd touch her face, press her thumbs into her cheeks. Then she'd lie on the floor, sobbing until I picked her up; but she'd fight me off, close herself in the bathroom, and I'd here the shower running for hours.

This is what he'll never understand:

The swift, instructive nature of a bomb. History becomes a single point in space—chronic sin chronic. Threading diachronic through a pinhead. Parole—his teeth; Langue, her cunt. This is how the modern world presents itself. Mark it: time and love and genealogy, and fuck it: every effort to convey this sort of reflex will result in tandem with the articulation of its opposite. Oh God, they cry, Oh God! Let us out of [hearing that, Alfred Jarry's zombie comes alive, feeding on the phlegm napkined off of Zizek's beard, while Marx and Harry Potter have a duel, leaving both with facial scars]! Only this: she could have loved him, maybe, if she'd never opened Baudrillard, never owned a mirror, never watched TV.

Not Him

He wasn't paying attention, so I put a finger in his mashed potatoes. Before he looked, I smoothed the potatoes with my fork to hide the hole. Millionaire was on TV. The question dealt with popular novels. Hey, he said, You should know this one. He dug at his potatoes, took a huge bite. I watched him chew, fascinated by his ignorance. It was sort of cute, the way he feigned an interest in my work. I said, I do Antebellum American lit, babe. Grisham's American, no? he replied, eyes on the screen. So I stuck another finger in his food.

Not Her

Don't cry, I'd say. I'm right here, I'd say. But where in that head of hers was she?

SQUARE 6

Her

We were watching the second Matrix movie, random Saturday night. That's Cornell West, I said. Who? he asked with popcorn in his mouth. I pointed, The black guy there with the afro. No, he said, I mean who's Cornell West? I looked at him and bit my lip. I watched his jaw move up and down. Then I licked my finger and twisted it in his ear. Without turning from the screen, he brushed my hand away. Stobbit, he mumbled and I lay my head on his shoulder. That was the happiest I've ever been.

Him

We took a weekend trip to Madison. We met some friends there. I said I liked the bike paths in the road. We ate sushi late at night. I made a few jokes about cheese. We listened to Joni Mitchell's "River" on the drive back. We watched "Elimidate" at home, and she kissed me once on the lips before we fell asleep. After that, nothing. She stopped; just stopped, everything. Not a touch, not even a smile. When I tried to talk about it, she'd say stuff like: I'm a clock face with no hands. She spent all her time writing a paper on Sound and the Fury. She didn't eat for days on end. She wouldn't let me see her naked. When I tried to hold her, she wouldn't even sigh, didn't bother anymore to pull away.

This is what he knew about her that she didn't even know about herself:

When pressed, she can't distinguish A. from P; she brings up N., or D., or M. and E., and says she "much prefers." Her dreams: the jetsam of a multi-mediated course in human history. She sees herself as someone else; the abject particle of failed equations with celebrity. She will lionize his cock in meditation; her yoga coach is cute like Maggie Gyllenhaal; behind her pessimism lies a secret faith in Dionne Warwick; sometimes she thinks about the shape and weight of boxing gloves, of telephones, of hats with brims; skyscrapers make her nipples erect; the desert makes her long for canopies, tents, picnics in the rain; she's a sycophant to those in charge; she seeks approval from everyone while criticizing the status quo; at night her toes get cold; sometimes, even, her protests turn to prayer.

Not Him

When I first met him, boy, I really thought we had a chance. I remember telling someone, though I don't remember who it was, I said, "Damn, you know, sometimes life just has a way of dropping magic in your lap." Now, bleh. Magic has a way of making itself disappear. Poof. Ta-fucking-da! Ex something comes nihilo.

Not Her

At the fourth of July fireworks display at Millennium Park, I thought to myself, Why the hell not? So I kissed a coworker named Rebecca. It was only once, and it wasn't really all that great. But it was something in the end.